Long-term safety is a precondition for final disposal – But how does the multi-barrier concept work?

Safety is a precondition for final disposal. The key to the final disposal of spent fuel is the long-term safety of the solution which is assessed and demonstrated with the Safety Case.

Radioactive materials are contained within several barriers which are mutually supportive, yet as inter-independent as possible; this guarantees that the failure of one barrier will not affect the isolation performance.

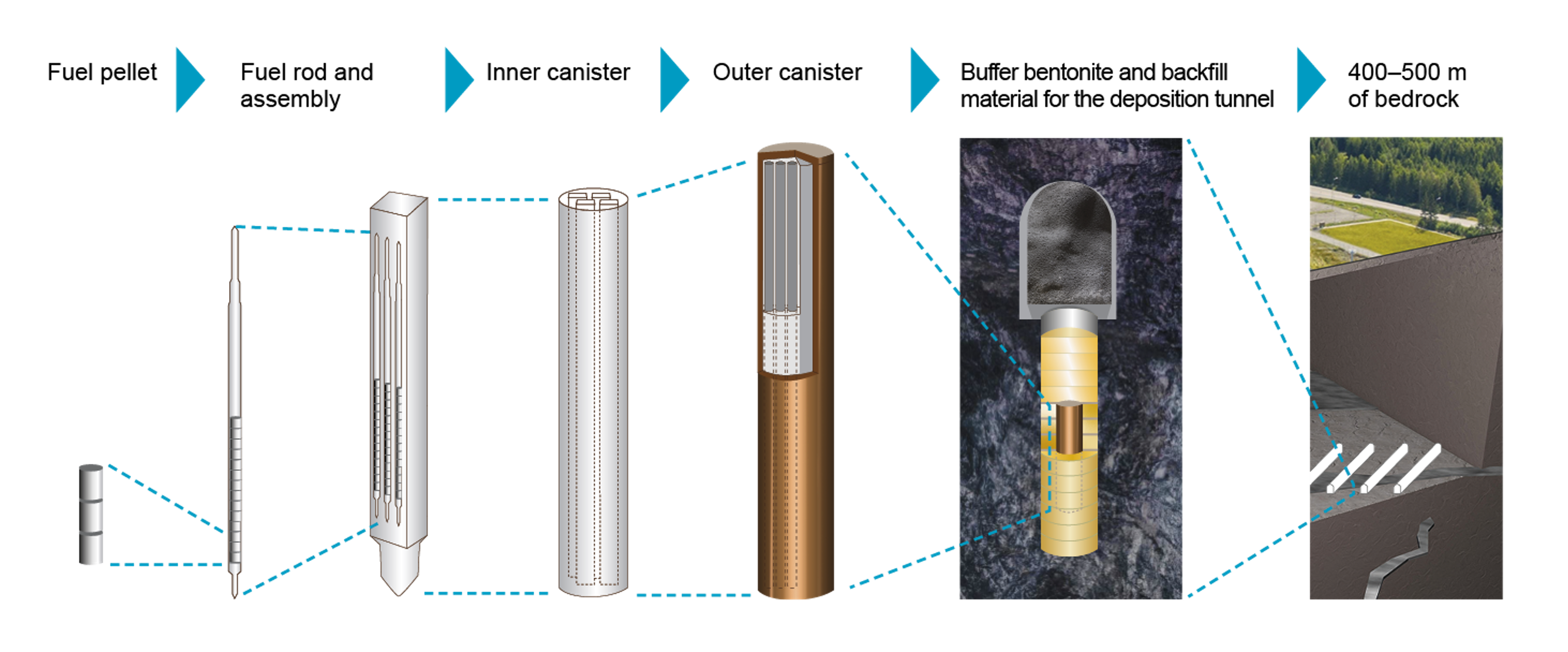

The first barrier in the multi-barrier concept is the ceramic uranium pellet which contains a little over three per cent of uranium. The pellet is enclosed in a metal fuel rod and the rod is enclosed by a metal cladding inside a fuel assembly.

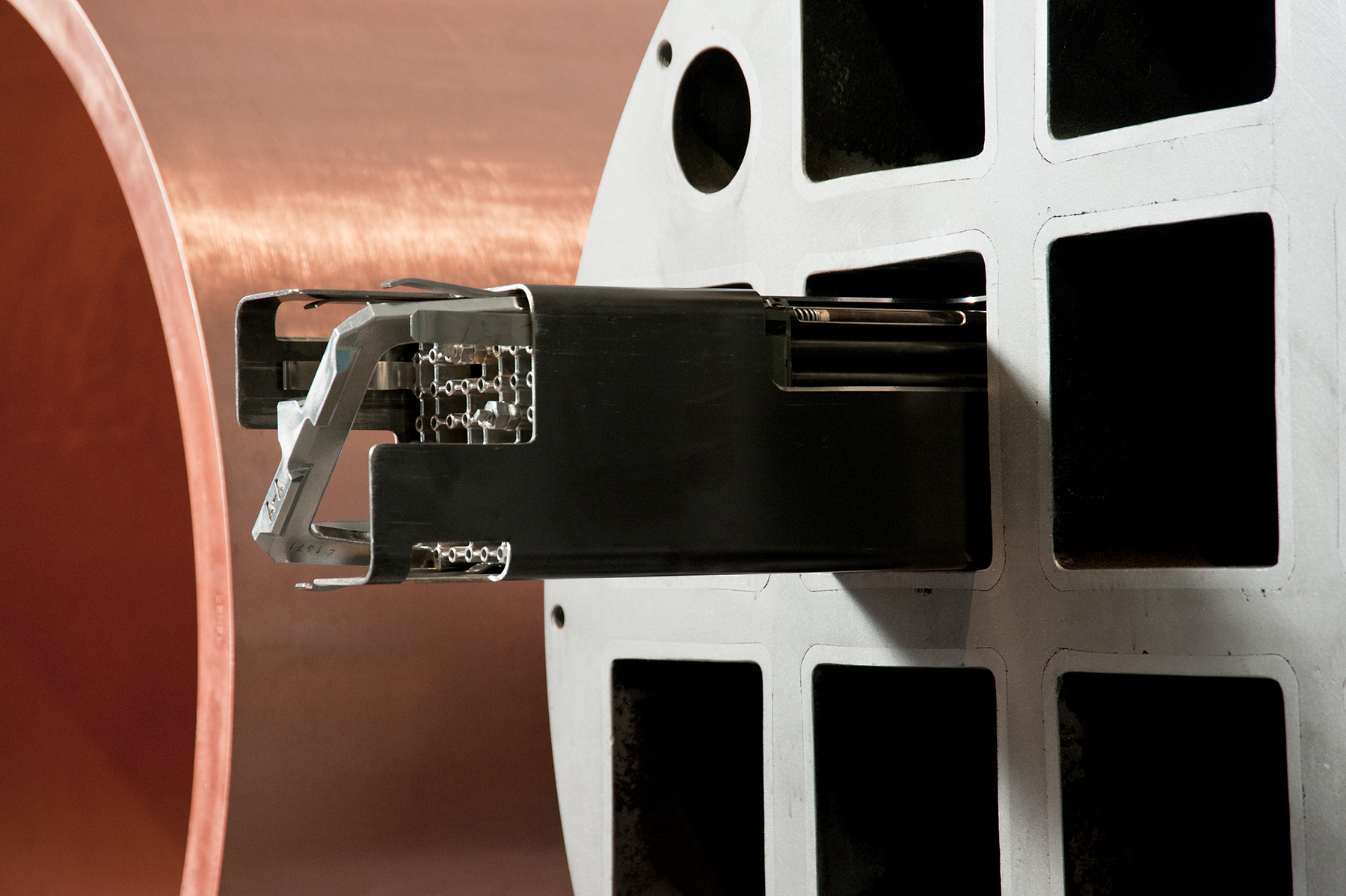

The fuel assembly is then placed inside the final disposal canister insert made of spheroidal graphite cast iron and finally, the insert is installed inside the outer copper shell of the canister. At this point, the radiation level on the canister surface is only about one hundredth part of the radiation measured on the surface of the fuel element.

For long-term safety, the key issues include the sustained integrity of the canister and the containment of the radionuclides inside the canister over the long term.

The canister placed in the final disposal deposition hole is covered with bentonite clay as a further barrier. People can safely walk on top of the deposition hole already at this point, with radiation levels close to natural background radiation. The final disposal tunnel is filled with backfill material and finally, the open tunnel areas are closed. The last one of the barriers consists of almost half a kilometre of Finnish bedrock.

The watertight, strong copper canisters are deposited in the bedrock at a depth of about 430 metres, separated from humans. They remain tight and safely contained inside the rock without any need for maintenance for a long period of time, until their content is no longer of any material harm to the organic nature.

Radiation level keeps decreasing

The radiation level of spent nuclear fuel also decreases relatively fast. When the fuel is removed from the reactor, it is first cooled in a pool next to the reactor for about one year and then transferred to the interim storage for spent fuel. At this point, the fuel has already lost 90 per cent of its radioactivity.

When the final disposal starts after about 40 years of interim storage, the radiation level of the spent fuel has decreased to just one thousandth part and the fuel is no longer self-heating.

Spent nuclear fuel is a toxic heavy metal which needs to be separated from the environment as well as humans even after it loses its radioactivity.

Principle of long-term safety defined in STUK Guide

The aspects of long-term safety are presented in detail in YVL Guide D.5 of the Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority of FinlandOpen link in a new tab. According to the Guide, the ingress of substances detrimental to long-term safety into the emplacement rooms shall be limited as much as practically possible, and their concentration within the emplacement rooms shall be monitored.

The upper limit of the annual radiation dose caused by final disposal over a period of several thousand years to the representative person is set to 0.1 millisieverts (mSv). The average effective annual radiation dose per person in Finland is 5.9 millisieverts (mSv).

Safety Case

According to the international definition, the safety case refers to all technological and scientific materials, analyses, observations, trials, tests, and other proof used to justify the reliability of the assessments made of the long-term safety of final disposal. For Posiva, this translates into the demonstration of the performance of the geological final disposal solution in the bedrock conditions of Olkiluoto, based on more than 40 years of research and tests.

Not affected by even major global changes

The design base applied to the long-term safety of geological final disposal comprises not only criteria related to nuclear and radiation safety, but also assessments of the various changes occurring in nature. For example, the Safety Case analyses the resistance of the final disposal solution to earthquakes, future ice ages over a period of up to a million years, and the loads caused by the icecap.

The construction of the final disposal facility in bedrock that is about 1,900 million years old requires careful and controlled underground building processes to ensure that the intact rock volumes and groundwater conditions remain favourable also after the conclusion of the final disposal operation.

The safety of the final disposal of spent nuclear fuel is assessed during and after the operational stage of the final disposal facility. The analysis period of long-term safety is divided into different time periods, from the about one hundred years long operational stage during which the final disposal tunnels are closed one after the other, to periods of the subsequent thousands and hundreds of thousands of years all the way to a million-year period.

Although it is not possible to ever analyse and assess all potential future courses of events in detail, the Safety Case provides a means to demonstrate that even based on a conservative assessment, the final disposal of spent nuclear fuel will not have any adverse effects on humans or the environment.

Text: Pasi Tuohimaa

Share